Updated on 20 April 2024

Laws and social norms in industrialised societies have been shaped by the metaphor of society as a factory and the metaphor of people as machines more than most people realise. In the emerging technoverse, biological life is perceived as becoming irrelevant. The many ways in which atomised nuclear families depend on abstract institutions is considered normal, and all those who depend on assistance from others in unusual ways are pathologised. Social power can be understood as the privilege of not needing to learn. As we live through the current human predicament we are well advised to understand capitalism as a collective learning disability that actively contributes to human and non-human suffering. A holistic social justice approach rather than a mechanistic rule based approach to collaboration between groups is at the core of the neurodiversity, disability, and indigenous rights movements.

- Fossil fuelled scientism of progress

- Social consequences of neoliberal ideology

- A social systems theory for the digital era

- The illusion of technocratic control

- Beyond the illusion of control

- Reflections with the vision of hindsight

- Inherent limitations of formalising social systems

- Evolutionary design

- Mental health is a function of communal health

- Collective learning disability induced by social power gradients

- Adopting a human scale aware precautionary principle

- Rediscovering the beauty of collaboration at human scale

- Conclusion

- References

Fossil fuelled scientism of progress

The preoccupation with technology and the exploitation of fossil fuels to expand industrial production accelerated following WWII, fuelling an illusion of infinite growth on a finite planet (Meadows et al. 1972). Anthropocentric confidence in technology and growth seems to have peaked in the 1980s, when neoliberalism was installed around the world as the future engine of wealth and prosperity.

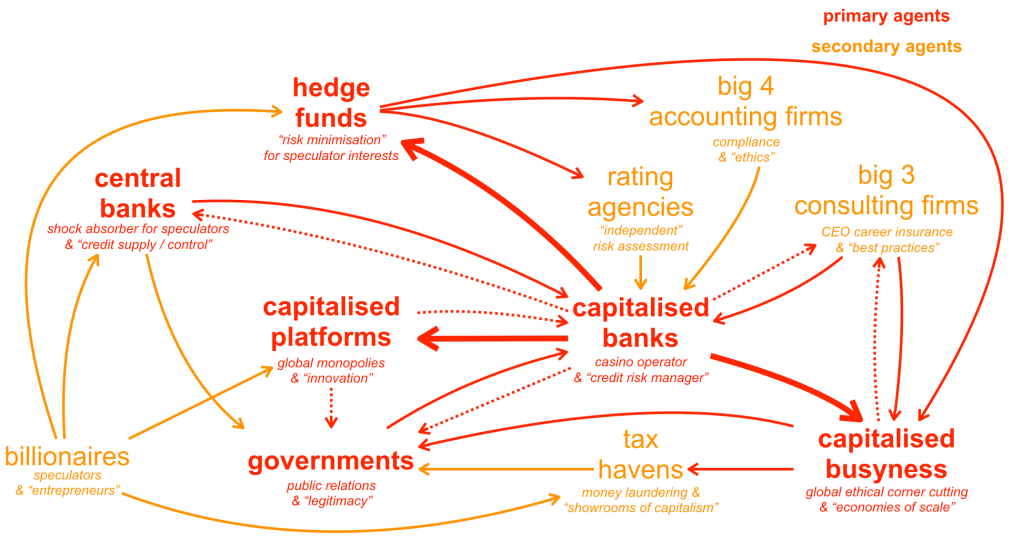

Under the hood, the neoliberal engine was powered by the availability of computers and software, and by the economic logic of Moore’s Law (1965). The entanglement of digital communication technologies and neoliberal economics can be understood by examining the evolution of the dominant and most profitable use cases for digital automation.

Initially, the automation of logistics afforded by computers, software, and robotics allowed the production of material goods to be increased without the need for additional workers. By the 1990s however, many wealthy Western countries had reached a level of material affluence, automation, and offshoring that made it difficult to generate further profits from industrial automation. Instead, the invention of networked computing and the Web opened up new opportunities for economic growth in the abstract, non-physical digital realm, which was sold to investors and entrepreneurs as a virtually unlimited territory that awaited to be conquered – powered by the magic of Moore’s Law and neoliberal ideology (Palmer 2006).

Economic activity and the focus of automation thus shifted into domains that were one or more levels removed from the physical realm, i.e. into various forms of financial speculation, including the development of complex derivatives and entangled bundles of financial products. This increased the leverage of capital and the velocity of financial transactions, culminating in high frequency trading, speculative asset bubbles, and in the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

Laws and social norms in industrialised societies have been shaped by the metaphor of society as a factory and the metaphor of people as machines more than most people realise. Humans are referred to as human ‘resources’, and human lives are assessed in terms of ‘net worth’ and ‘purchasing power’ (Hedges 2021). As these metaphors have expanded into the digital realm, they have not only warped our relationship with the natural world and our conception of humanity. They have also led to technocratic cults, in which corporations have taken on the role of sacred places of worship, and in which CEOs are the high priests, praising the divine qualities of artificially intelligent technologies (Rushkoff 2023). In the emerging technoverse, biological life is perceived as becoming irrelevant. When society is a factory, the only things that count in are things that can be measured (Deming 1982, 1984).

It is no coincidence that Taylorism, so-called scientific management, was conceived in the wake of the invention of the steam engine and machine assisted manufacturing, to complement the the laws of physics that governed the mechanics and the productivity of the machines on the factory floor.

Formalising the discipline of economics with mathematical tools allowed the scientific approach to managing humans to be extended to the scale of nation states – another conceptual building block for organising human activities in industrialised societies. There are a number of parallels between the impact of the development of economic theories on human society and the social impact of the development of the Internet.

Neither the Internet nor economics draw directly on an evidence based understanding of physics, biology, and human behaviour. Both the Internet and economic theories are best understood as prescriptive rather than as observational tools, as language systems that are based on specific European and North American cultural conventions that are assumed as ‘sensible’ (common sense) or ‘obvious’ (self-evident). With these language systems in place we can measure data flows and economic performance, but only in terms of the scope and the preconceived categories afforded by the formal protocols and languages (Rees 2023), (Alkhatib 2021), (Bowles 2016).

The introduction of a formal economic language system and the introduction of formal protocols for digital communication have shaped human culture around the social ideologies espoused by early industrialists and early information technology entrepreneurs. Over course of the last two centuries governments have become increasingly dependent on economists and information technology entrepreneurs in order to understand and engage with society, and also to understand what what technological options are on the horizon, to the extent that corporations directly advise heads of states (Pennington 2023). In this process anything that lies beyond the scope of what is deemed relevant or acceptable is discounted as non-essential or unproductive.

In the multiple bottom line approaches that have become popular in the context of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, the conveniently simplistic thinking becomes evident when metrics from the natural world are translated into monetary metrics, as if a monetary number can adequately represent the loss of biodiversity and the destruction of entire ecosystems in the name of economic progress.

Astute observers have been lamenting the chasm between digital hype and the way that technology manifests in our lives for decades (Nelson 1999). Based on what we have seen so far, we have to conclude that the design of digital services, when conducted within the bowels of transnational corporations, with millions and in some cases billions of users, without giving these users the ability to shape the design, is a form of corporate social engineering, whether intentional or not.

Social consequences of neoliberal ideology

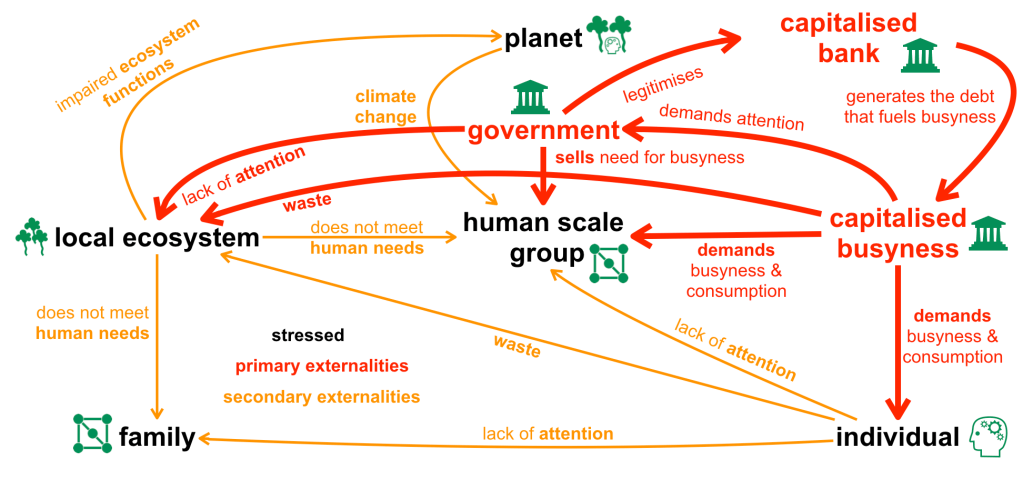

The institutions and accepted cultural practices of the modern globalised world that consistently prioritise free flow of capital are traumatising the entire planet. The polycrisis, which is the modern human predicament that we are all living through, can be illustrated with three short cultural narratives:

- ‘Prayer for the Earth: An Indigenous Response to These Times’ (Rushworth 2024).

- The effects of the one-dimensional logic of global capital, illustrated by looking at the overall cultural and ecological impact on the small island nation of Nauru (Çenet 2023)

- The effects of the arbitrary anthropocentric cut-off points (Bettin 2024) of the bell curve in the social realm, illustrated by looking at the overall cultural and ecological impact on a small island nation such as Tuvalu (Malie, G. et al. 2023).

These narratives illustrate the cognitive and emotional blindspots that are baked into ‘normality’.

The life destroying impact of the modern human obsession with measuring, and then reducing the dimensionality of all problem spaces to the one-dimensional metric of financial capital can hardly be overestimated. The classic novel Flatland (Abbott 1884) comes to mind. Flatland illustrates the confusions and the loss of meaning created by reducing four dimensional spacetime to two spatial dimensions and the dimension of time, i.e. a reduction of a four dimensional problem space to three dimensions.

The semantic chemical building blocks of the biological world we inhabit contain thousands of dimensions. If we add emergent phenomena at larger levels of scale, we live in a world of millions and billions of semantic dimensions. We all have our own unique way of making sense of the world, from the perspective of the relational ecology of care that surrounds us.

And yet, we live in a world where human social affairs, across all levels of scale, are dominated by a one-dimensional metric. Some still recognise that there is biological life beyond finance, but our minds have been warped by extensive exposure to a one-dimensional metric.

The Anglosphere is leading the world in legal engineering and perception management.

A social systems theory for the digital era

The pioneering work on a universal social systems theory by Niklas Luhmann (JSTOR 2021) in the 1970s through to the 1990s provides a deep and insightful analysis of the effect that the emergence of modern one-to-many communication technologies, i.e. mass media, has had on the evolution of social systems. Many of Luhmann’s insights have only gained relevance in our era of ubiquitous many-to-many communication technologies, i.e. digital social media, which are controlled by global technology corporations.

Luhmann’s perspective and working method were informed by his background as a legal scholar. His work relied heavily on his idiosyncratic ‘Zettelkasten’ note-taking method, over the course of thirty years resulting in a set of drawers with over 90,000 index cards for his research. A digitised archive of all his index cards is available online in the Niklas Luhmann Archiv (University of Bielefeld 2024).

In Niklas Luhmann’s theory of social systems, culture is analysed and constructed at a population level scale that transcends human cognitive and emotional limits, in the form of explicit communication between abstract social subsystems, such as the media system, the legal system, the family system, the economic system, etc.

The illusion of technocratic control

Attempting to explain cultural evolution of socially powered-up super-human scale societies from a top-down, outside-in perspective is appealing from the perspective of the established institutional landscape. The top-down approach prioritises the perspective of so-called authorities over the perspectives of the thousands and millions of local and cosmolocal (Niaros et al. 2020) communities that shape lived experiences at human scale.

On the surface, mass media and digital social media seem to expose billions of humans to billions of perspectives. Upon closer examination this assumption turns out to be an oversimplification that obscures important systemic social power differentials. A small number of mass media organisations and social media celebrities have audiences that measure in the millions and billions, but at the receiving end of all acts of communication, all humans are constrained by cognitive and emotional limits, and by the physical limit of days that are constrained to 24 hours. By design, mass media and social media algorithms guarantee that a very small number of perspectives benefit from being thousands or millions of times more visible than others (Metzler et al. 2023).

Digitally connected humans are exposed to continuous communication overload, including the sensory overload generated by digital technologies. Niklas Luhmann’s theory is well suited for understanding the effects of the small number of perspectives that are amplified by digital algorithms. It is less well suited for understanding the bottom-up development of social movements that involve billions and trillions of communication acts at human scale.

With the help of machine learning algorithms, the latter factor of cultural evolution can be analysed to some extent, but in the current legal landscape, data usage rights and access limitations effectively only makes this capability available to the dominant players in the institutional landscape. The questions of interest for these players are by definition limited to the comfortable sphere of discourse that is framed by the world view of powered-up authorities. In fact, any analytical results that may threaten dominant cultural narratives are likely to be fed into the re-configuration of social medial algorithms, in ways that dampen inconvenient perspectives and that reinforce dominant cultural narratives.

By design, thoughtful critical narratives are highly unlikely to reach the wider public within non-judgemental framings and containers. Instead, the operators of social media platforms benefit greatly from simplistic attention grabbing narratives of all colours, thereby allowing established authorities to promote their perspectives as the ‘voice of reason’, consistently in favour of perpetuating the social power structure of the capitalist institutional landscape (Fischer 2009).

Beyond the illusion of control

Regardless – or rather due to – the way in which social medial algorithms evolve and the ways in which mass media are tied to dominant cultural narratives, peer-to-peer (P2P) communication at human scale is being used by billions of people, including encrypted and anonymous forms of communication. This somewhat less publicly visible infrastructure, which is increasingly de-centralised, diverse, and distributed, is the substrate in which social movements increasingly operate.

Human scale P2P collaboration ‘Together we know everything, together we have everything’ (P2P Foundation contributors 2023) is what remains after subtracting all the communications between mass media organisations, social media celebrities, big governments, and corporations. In contrast to the pre-Internet era, such collaboration has become cosmolocal, and is catalysing intersectional solidarity and global sharing of lived experiences on the margins of societies, and across social movements.

The diversity and the many millions of cosmolocal collaborations do not neatly fit into any finite comprehensible number of categories, and thus they escape analysis within Luhmann’s framework.

In Luhmann’s theory the focus is on communication between abstract systems, each of which may include many social agents, e.g. institutions and people. In this theory semantic integration between systems occurs in the explicit communication between systems.

This is a pragmatic approach to collective sensemaking in a powered-up social world of super-human scale systems in which one-to-many communications play a substantial, if not the dominant role, in maintaining cultural inertia. Relevant metrics include opinion polls, votes, and economic transactions. Typical outputs include persuasive communication, laws, and social norms. Key tools include mass media and social media.

Luhmann assumes culture is encoded in explicit communication between systems of social agents (Strauch 1989). In this context social agents can be individuals or institutions at any level of scale.

The public digital realm is entirely socially constructed in terms of explicit communication and explicit encoding of many rules. Therefore it lends itself to analysis with the help of Luhmann’s systems theory of society.

Strengths

- Analysis of socially constructed large scale systems involving millions of people.

- Awareness of human cognitive limitations.

- Awareness that anthropocentric control is an illusion.

- Awareness that all large scale human decisions are likely to cause harm, often out of immediate sight of the decision makers.

- Staying clear of moralising and recognising the dangers of moralising.

Weaknesses

- Lack of acknowledgement of the role of collaborative niche construction within the evolution of all living ecosystems.

- Lack of awareness of the limits of human scale, the diverse possibilities and dynamism that open up at human scale, and how corporate and state controlled large scale digital systems exclude all these possibilities, and, with the help of protocols and algorithms, cultivate public perceptions of both paradigmatic inertia and insignificant yet somehow dangerous irritants.

- Lack of awareness of the innate collaborative tendencies of humans.

- Naive belief that socially powered-up systems such as markets can channel self-interest into collective benefits.

- Due to a focus on second order cybernetics, limited focus on the feedback loops between socially constructed super-human scale systems and biological and ecological systems, including the extent of ecological externalities, which already became apparent with the Limits to Growth, a weakness that could be rectified by considering higher order cybernetics (Yolles 2021), and with the help of the recursive formalism of higher order category theory (nLab 2024).

The Australian human scale permaculture pioneer David Holmgren (2023) would likely see similar limitations in Luhmann’s theory. The diversity and the many millions of cosmolocal collaborations today do not neatly fit into any finite comprehensible number of categories, and thus they escape analysis within Luhmann’s framework. Collaborations amongst permaculture practitioners are a good example.

Reflections with the vision of hindsight

Forty years ago we had less scientific evidence regarding all the factors that we can identify as weaknesses in Luhmann’s theory with the vision of hindsight. But already in the late 1990s, during Luhmann’s lifetime, educated people had access to plenty of indicators and warning signs, that all along indigenous people intuitively understood many of the flaws in our powered-up and hypernormative society.

Collective cognitive dissonance in WEIRD societies (Henrich 2021) has been rising, yet has been kept out of the public discourse, precisely because of the way the modern media system functions in entirely socially constructed super-human scale systems, exactly as described by Luhmann. This is how WEIRD became truly WEIRD Theatre, i.e. WEIRDT (Bettin 2023c), and how hypernormative social norms and laws dehumanised, pathologised, and criminalised growing segments of the population, to an extent that has started to visibly erode the social license of established institutions and the associated paradigmatic inertia from the bottom up.

Like Marx, Luhmann is an excellent analyst. Unlike Marx he avoids speculating about the future. To avoid gambling with the future of humanity and to avoid unleashing even greater harm on the planetary ecosystem (Michaux 2023), we can build on the strengths of Luhmann’s insights as well as on what we now recognise as weaknesses in his theory.

From what is known about Luhmann and his lifetime project of conceptualising the social world (Moeller 2021), (Schmidt 2021), (Morgner 2022), his perseverance, his idiocyncratic sense of humour, and his unique system of working, today many in the Autistic community would likely regard Luhmann as neurodivergent.

Inherent limitations of formalising social systems

The introductory lecture ‘Introduction to Luhmann & Systems Theory’ (Tohme and Gangle 2021) outlines how category theory can be used to formalise Luhmann’s theory.

Systems are human mental abstractions, they live in human minds, and via communication, especially dialogues, they incrementally find their way into other human minds with varying levels of fidelity (Lakoff and Johnson 1981). Luhmann’s theory focuses on the explicit communication between abstract systems, ignoring that these abstractions can only come into social circulation with the help of symbolic language, and that different people may have different mental models of a specific system (Milton 2012).

In the above introductory lecture, the abstract conceptual nature of systems is illustrated in the observation that ‘the system needs the environment, the environment does not need the system.’

The very definition of systems like the the legal system, the media system, the economic system, the family system, etc. will always be fuzzy, and the commonalities tend to be hard to pin down. The legal system is one of the least fuzzy systems, as only laws that are written down and have been enacted count. In contrast, the definition of a system like the media system is much less well defined and less formalised – yes, all communication acts can be identified, but which ones involve agents that are part of ‘the media system’?

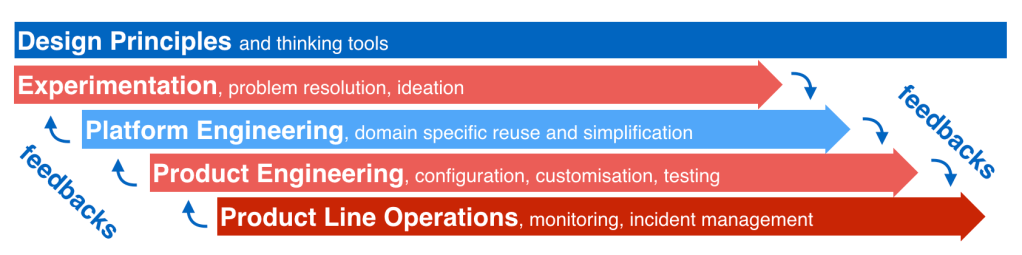

Evolutionary design

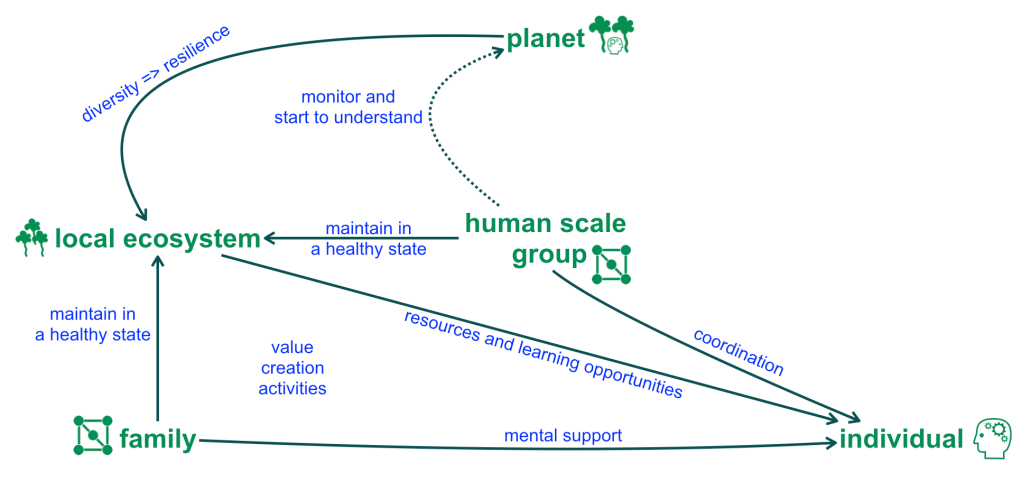

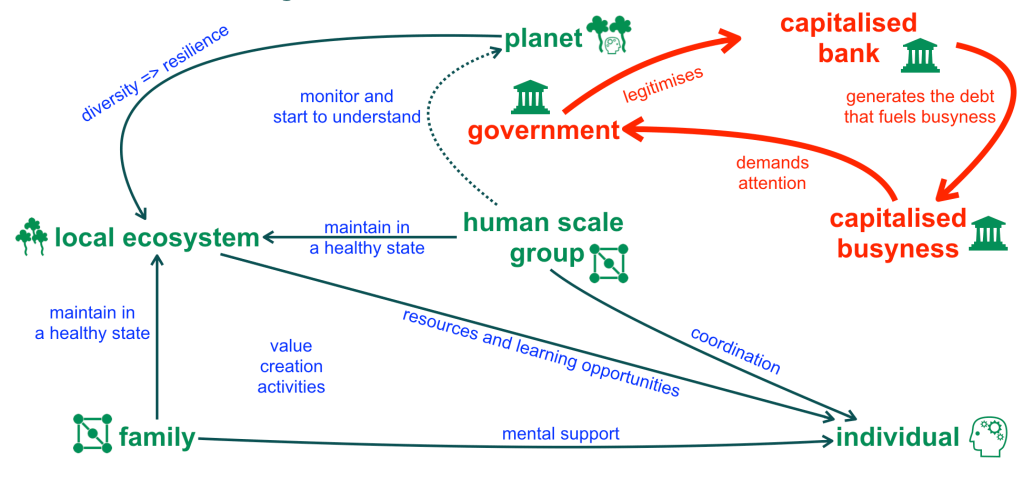

Evolutionary design (Bettin 2021a) is an approach to sensemaking and adapting sociotechnological systems based on the principles of cultural evolution that can be derived from anthropological observations and from archaeological evidence about human scale societies that predate the emergence of civilisations.

In evolutionary design the notion of intentional design is entangled with the concept of evolution within an ecological context, resulting in a profound shift in underlying assumptions about the ability of human institutions to reliably produce predictable design outcomes, especially at larger scales, at which human cognitive and emotional limits come into play.

Cultural evolution entails not only the evolution of collaborative relationships and supporting tools within a group, but also the evolution of collaborative relationships between groups with many cultural commonalities, as well as between groups with few cultural commonalities.

In Evolutionary design the focus is on communication between concrete social agents, specifically on the evolution of shared understanding and knowledge co-creation, recognising that knowledge may pertain to the system or to the environment, and that the internal models that agents maintain act as the semantic integration points between systems. Many of these semantic integrations are not visible as explicit communication but show up in the form of tacit knowledge, i.e. as unobservable and often subconscious processes within each social agent.

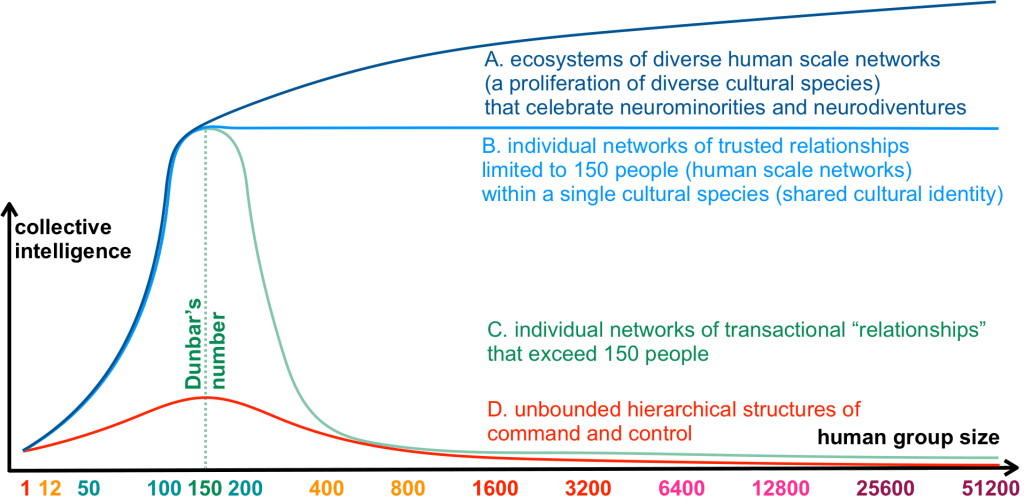

This is an approach to collective sensemaking at human scale that aims to maximise shared understanding and long-term collaborations, which in turn depends on the ability to nurture psychological safety and maintain lifetime relationships. Relevant metrics are hard to quantify objectively and include mutual trust, wellbeing, and biodiversity. Typical outputs include tacit and explicit models of shared understanding of the world, not limited to social norms. Key tools include de-powered dialogue (Bettin 2023a), Open Space (Owen 2008), prosocial principles (Ostrom 2015), and design justice principles (Design Justice Network 2018).

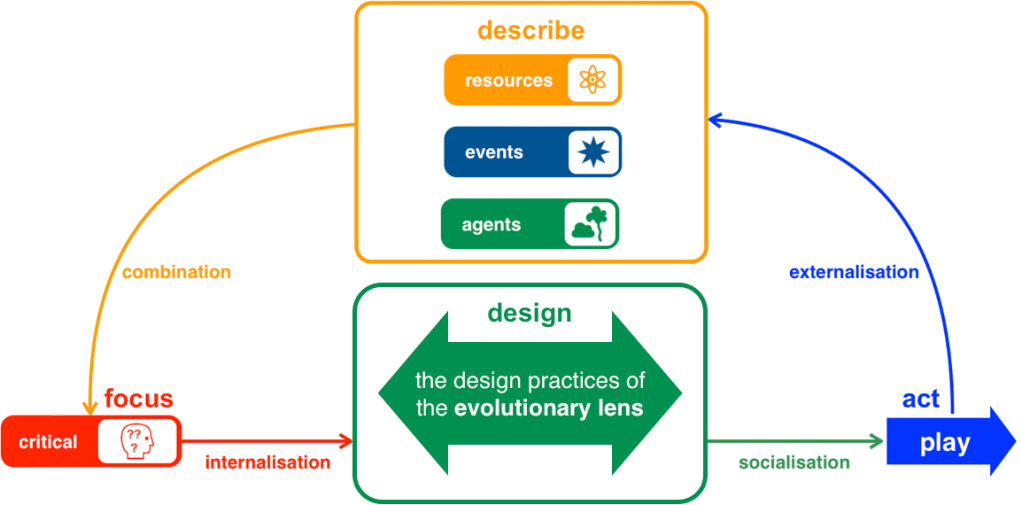

The evolutionary design approach builds on experience with the bottom-up Socialisation, Externalisation, Combination, Internalisaton (SECI) model of knowledge co-creation (Nonaka et al. 2008), and on collaboration in Open Space.

The principles that underpin evolutionary design complement the social systems theory by Niklas Luhmann. Whilst the principles of evolutionary design have been distilled from thirty years of personal experiences with cultural evolution in human scale groups and between human scale groups (Bettin 2020), informed by foundational principles for the emergence of nested complex systems (S23M 2023) from a bottom-up, inside-out perspective, Niklas Luhmann starts with a top-down, outside-in perspective.

In contrast to Luhmann’s theory, the multi-level approach of evolutionary design does not assume completely functionally closed systems. Instead of the social system as a whole including a model of itself, evolutionary design recognises that each social agent within a social system is assumed to maintain an internal model of the whole social system and the environment. These internal models are always simplifications, as all agents are understood to have cognitive and sensory limits. In both approaches social agents may be part of one or more systems.

In evolutionary design, culture is experienced and co-created at a human scale that is comprehensible for humans, adapted to human cognitive and emotional limits, in the form of shared understanding, by nurturing trustworthy lifetime relationships.

In complex, socially powered-up empires and modern nation states, i.e. hierarchically structured large scale societies, which are governed by abstract institutions with formal authority to make decisions that affect millions and sometimes even billions of people, both approaches have their place and complement each other.

Mental health is a function of communal health

The modern disciplines of psychology Fechner (1860) and psychiatry Reil (1808) are a product of the European industrial era, focused on helping individuals to cope with the mental burden and cognitive dissonance that is generated by having to function – or pretending to be functioning – as a cog in the industrialised machine. The problems of alienation are as old as industrialisation. Karl Marx is famous for writing extensively about the topic (1844).

After decades of outsourcing and offshoring, many of the so-called rich nations are no longer heavily industrialised in the classical sense of producing material goods. Instead, many people are employed in the so-called service sector, and many of those who have attained higher levels of education, i.e. certified professionals, work in bullshit jobs (Graeber 2018). Those performing such jobs feel that their job is largely meaningless, and in many cases, that it actively contributes to the modern human predicament.

This is the result of an oxymoronic economic system that literally optimises for the appearance of busyness. This is not a joke, and many marginalised people are fully aware of this fact.

The specific challenge that mental health professionals face is a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual American Psychiatric Association (2013) that reflects the cultural bias of Western ‘normality’, in which sanctified bullshit (Spicer 2020) is the informational fuel that runs the so-called economy. Therapists and psychiatrists have the best intentions, and most genuinely want to help people, but whatever assistance they provide, at the latest when their patients are sent back into the economic engine to ‘perform’ in the so-called economy that is liquidating the living planet, they will again suffer from predictable mental health problems.

Surviving on the edges of modern society is an art. The arts and regular immersion in genuinely safe Open Spaces help us imagine and co-create ecologies of care in which care and mutual aid are the primary values. Healthy artistic and Autistic life paths by necessity differ from ‘normality’ (AutCollab 2024).

There is an urgent need to catalyse Autistic collaboration and to co-create healthy Autistic, artistic, and otherwise neurodivergent whānau, i.e. extended chosen families, all over the world. Marginalised people depend on assistance from others in ways that are pathologised in hypernormative WEIRD societies (Bettin 2019). However, the many ways in which atomised nuclear families and individuals depend on abstract institutions in far away places is considered ‘normal’. The endless chains of trauma must be broken.

Collective learning disability induced by social power gradients

The story of infinite economic growth and technological progress portrays a completely delusional and scientifically impossible world (Meadows 1972), (Rees 2023), which not only ignores biophysical limits, but also human cognitive and emotional limits. Nurturing the human capacity to extend trust to each other, and engaging in the big cycle of life as part of an ecology of care beyond the human is the biggest challenge of our times.

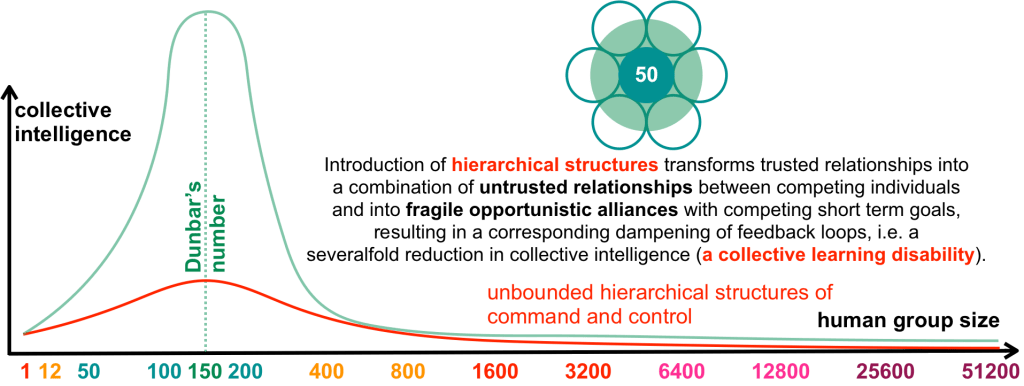

Social power can be understood as the privilege of not needing to learn, and taking the liberty of making decisions that affect large populations, in complete ignorance of our own individual human cognitive and emotional limits, which prevent us from fully comprehending the needs and unique circumstances of thousands of diverse communities and millions of people (Bettin 2021b).

Stepping back, looking across all empire building civilisations, the collective learning disability induced by powered-up social relationships can be traced to the following ways of systematically distorting and dismissing lived experiences:

- Oversimplification – by reducing complex problem spaces to a much lower (one!) dimensional space. This is the commonality across all pyramidal systems of power – there is one perspective that dominates over all others (Shiva 1996).

- Inducing a systemic power differential – by distorting the oversimplified one dimensional metric with the notion of ‘interest’. This is the religion of economics (Graeber 2011).

- Watering down the precautionary principle – via cognitive blind spots created by the arbitrary normalising cut-off points of the bell curve in the social realm. Example: entire island nations completely get ignored until they are doomed. Their local existence is deemed ‘insignificant’ in relation to what happens in the so-called ‘real’, i.e. the big ‘normative’ world where all decisions are made. This is the scientism that is blooming in the era of big junk data.

- Systematically exploiting the ambiguities of linear narratives – by nominating a convenient ‘authority’ for interpretation. For a current example, we only need to look at the way Julian Assange is treated by the British Crown. Last century the world had Soviet dissidents. This century the United States are producing American dissidents. The Anglosphere is ‘leading’ the world in legal engineering and perception management.

- Systematically exploiting cognitive blind spots – created by translations between different languages, again by nominating a convenient ‘authority’ for interpretation. Aotearoa is a poster child for this approach (Network Waitangi Whangarei 2012). This goes hand in hand with implicit assumption that some languages are more ‘primitive’ than others.

- A misguided focus on ‘winning’ arguments – rather than engaging in omni-directional learning to better understand each other. This is the bullying that is taught in business schools, i.e. the art of marketing, sales, and corporate power politics. The most honest conversation that I have had on this topic was with a former technology investor who describes business schools as ‘places that train people how to become a bad person’. My own attempts at educating MBA students in the neurodiversity paradigm were also disillusioning and traumatising.

None of this is new. The old Daoist scholars such as Lao Zi and Zhuangzi knew as much from lived experiences with powered-up empires over 2,500 years ago. The elements above are the cultural foundation on top of which it becomes possible to cloak highly coersive and abusive ‘normalisation’ therapies such as Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) as evidence based best practice (AutCollab 2021).

Adopting a human scale aware precautionary principle

On the basis of the evidence available to us today, we are well advised to fully acknowledge human limitations, including the limitations of human science and technologies conceived by humans. This entails adopting a scale-aware precautionary principle in all human endeavors:

At small (human) scales, practicing a high level of autonomous communal self-governance and applying a political conception of the precautionary principle: ‘Communal decision making in Open Space, supported by an advice process and mutual trust, should incorporate a margin of safety; activities should be limited below the level at which no adverse effect has been observed or predicted (margin of safety)’.

At large (super-human) scales, respecting the sanctity of the living planet, and applying a strict, science based conception of the precautionary principle: ‘Activities that present an uncertain potential for significant harm should be prohibited unless the proponent of the activity shows that it presents no appreciable risk of harm (prohibitory)’

Together, the two parts of the scale-aware precautionary principle imply that no community, regardless of scale, is entitled to conduct an activity that presents an uncertain potential for significant harm beyond small (human) scales.

To avoid the potential for unlimited harm, the scale-aware overarching precautionary principle tells us that social governance should never be placed in the hands of any powered-up person or institution with super-human scale decision making abilities.

A principle based and scale-aware social justice approach rather than a rule based approach to collaboration between groups is at the core of the evolutionary design approach that has been distilled from a range of sciences and transdisciplinary practices, including from the intersectionality between the neurodiversity, disability, and indigenous rights movements (Walker 2013, 2014), (Bettin 2023b). The evolutionary design approach is compatible with Luhmann’s theory in that the smallest unit of knowledge creation is a dialogue within or between systems.

Rediscovering the beauty of collaboration at human scale

We currently live in traumatising super-human scale societies.

There’s a “pervasive warlike culture” in the U.S. that leads us to approach just about any major issue as if it were “a battle or game in which winning or losing is the main concern,” she wrote. It’s a deeply entrenched cultural tendency that has shaped politics, education, law, and the media.

– Kate Yoder, War of words, (2018)

Growing numbers of marginalised people are involved in de-powering and co-creating alternative human scale social systems and communities (Bettin 2023e), whilst at the same time still interacting with super-human scale powered-up institutions out of the necessity to survive (Bettin 2023d).

The evolutionary design approach infuses social construction with:

- Lessons from our current understanding of biological ecosystems and organisms.

- The scale aware precautionary principle that reflects the timeless patterns of human limitations, which become visible when synthesising the insights from anthropology, archaeology, and history, including the rise and inevitable fall of all powered-up civilisations.

Individual social agents (organisms) are not only participants in a system, within ecological and biological processes they are also complex systems themselves, resulting in a structure of nested systems. For example, a mammal can be understood as a collection of interacting subsystems, i.e. the circulatory system, the nervous system, the mental system (all the mental models of the environment), the digestive system, etc. Each of these subsystem consists of specific agents (organs and cells). Whilst Luhmann’s theory could be used to describe the communication between these systems in abstract terms, evolutionary design is also equipped to describe the communication between specific organs and cells, and allows us to take a holistic approach to human wellbeing at human scale that is compatible with our evolutionary history.

Innovation and cultural change can only be transformative if it substantially redefines social norms and so-called best practice (de Decker 2022), and for this we need appropriate conceptual tools (Bettin 2017), including therapies that help tackle the modern addictions to social power and convenience, to overcome cultural blind spots and expand the sphere of discourse.

Conclusion

Nearly all our current platforms and applications in the digital realm are socially powered-up by the religion of the invisible hand, in contrast to biological ecosystems and organisms. As we live through the current human predicament we are well advised to understand the religion of the invisible hand as a collective learning disability that actively contributes to human and non-human suffering.

All of the above is just a long way of explaining what many indigenous grandmothers have understood about human scale all along, without needing to resort to modern science and modern social theories (Angarova 2023):

“Leave us alone, we know what we’re doing.”

References

Abbott, E. A. (1884) Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/201 .

Alkhatib A. (2021) ‘To Live in Their Utopia: Why Algorithmic Systems Create Absurd Outcomes. Why Algorithmic Systems Create Absurd Outcomes.’ CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’21), May 8–13, 2021, Yokohama, Japan. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764. 3445740

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR).

Angarova, G. (2023) ‘Understanding Suffering and Knowing Our Place.’ Holding the Fire: Episode 4. Resilience.org. October 2023.

AutCollab (2021) Ban of all forms of Applied Behaviour Analysis. https://autcollab.org/aba/ .

AutCollab (2024) Ecologies of Care. https://autcollab.org/knowledge-repository/ecologies-of-care/.

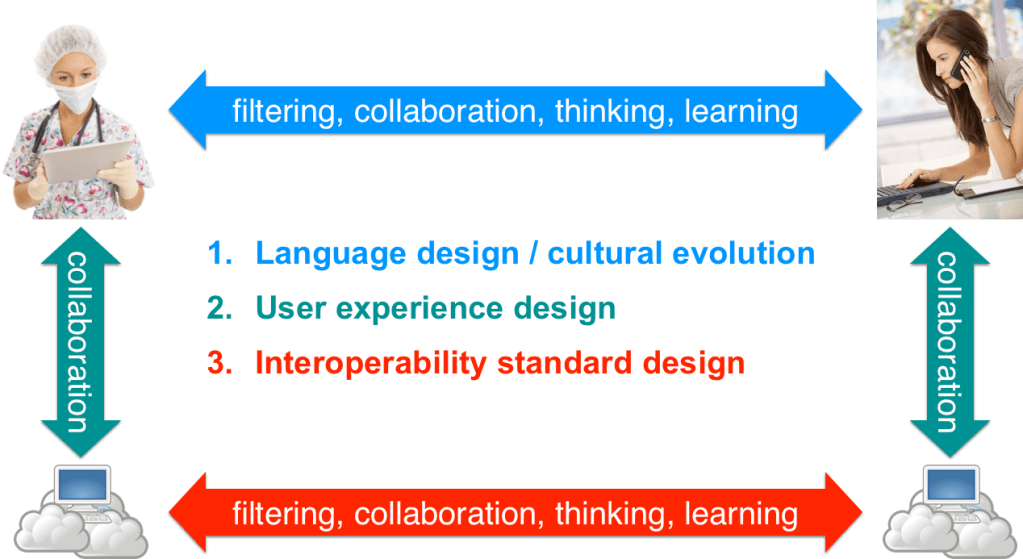

Bettin, J. (2017) ‘Designing filtering, collaboration, thinking, and learning tools for the next 200 years.’ Cultural Evolution Society Conference, Jena, Germany. September 2017. https://s23m.com/ces2017/index.html.

Bettin, J. (2019) ‘Celebration of interdependence.’ Autcollab.org. November 2019. https://autcollab.org/2019/11/13/celebration-of-interdependence/ .

Bettin, J. (2020) ‘Autistic people – The cultural immune system of human societies.’ AutCollab.org. April 2020.

Bettin, J. (2021a) ‘Evolutionary Design.’ https://jornbettin.com/2021/08/15/evolutionary-design/ .

Bettin, J. (2021b) The Beauty of Collaboration at Human Scale. Timeless patterns of human limitations. S23M.

Bettin, J. (2023a) ‘De-powered dialogue.’ AutCollab.org. November 2023. https://autcollab.org/2023/11/28/de-powered-dialogue/ .

Bettin, J. (2023b) ‘Intersectional solidarity and ecological wisdom.’ AutCollab.org. December 2023. https://autcollab.org/2023/12/09/intersectional-solidarity-and-ecological-wisdom/ .

Bettin, J. (2023c) ‘unWEIRDing Autistic ways of being’. AutCollab.org. November 2023. https://autcollab.org/2023/11/03/unweirding-autistic-ways-of-being/ .

Bettin, J. (2023d) ‘Surviving + De-powering + Thriving’. AutCollab.org. October 2023. https://autcollab.org/2023/10/30/surviving-de-powering-thriving/ .

Bettin, J. (2023e) ‘De-powering human societies.’ https://jornbettin.com/2023/05/18/de-powering-human-societies/.

Bettin, J. (2024) ‘Life defies the dehumanising cut-off points of the bell curve’. AutCollab.org. February 2024. https://autcollab.org/2024/02/21/life-defies-the-dehumanising-cut-off-points-of-the-bell-curve/ .

Bowles, S. (2016) The Moral Economy: Why Good Incentives are no Substitute for Good Citizens. Yale University Press.

Çenet, R. (2023) ‘Visiting the Fattest, Most Cigarette-Addicted and Least Visited Country’. November 2023. https://youtu.be/x1KrGZRzVGY.

de Decker, K. (2022) ‘De-Electrify everything’. Estonian Green Movement’s Degrowth summer school. August 2022. https://youtu.be/GqcMnrUWNM0.

Deming, W. E. (1982) Out of the Crisis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Deming, W. E. (1984) ‘The 5 Deadly Diseases.’ 1984. Deming Institute. https://youtu.be/2F1rhik2_X0.

Design Justice Network (2018) ‘Design Justice Network Principles.’ https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles .

Fechner, G. (1860) Elemente der Psychophysik. Leipzig : Breitkopf und Härtel.

Fischer, M. (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books.

Graeber, D. (2011) Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Melville House Publishing.

Graeber, D. (2018) Bullshit Jobs : A Theory. Penguin.

Hedges, C. (2021) ‘The Cult Of The Self.’ April 2021. https://youtu.be/QZIVQ8ExqEY .

Henrich, J. (2021) ‘The Weirdest People in the World. How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous.’ Penguin Press.

Holmgren D. (2023) ‘Small and Slow Solutions – Permaculture Design.’ The Great Simplification #96. October 2023.

JSTOR (2021) ‘Unlocking Luhmann: A Keyword Introduction to Systems Theory’, pp. 259-274 (16 pages). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2f9xsr5.72 .

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1981) Metaphors We Live By. The University of Chicago Press.

Malie, G. et al. (2023) ‘A country being lost to rising sea levels.’ Channel 4 News. December 2023. https://youtu.be/H-ar5drhjzU .

Marx, K. (1844) ‘Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte aus dem Jahre 1844’ (the Paris Manuscripts).

Meadows, D. (1972) The Limits to growth; a report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. A Potomac Associates book.

Metzler, H. et al. (2023) ‘Social Drivers and Algorithmic Mechanisms on Digital Media.’ Perspectives on Psychological Science OnlineFirst. July 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231185057 .

Michaux, S. (2023) ’Industrial transformation away from fossil fuels will not go as planned.’ Part 1: https://youtu.be/iqjsPa8bUaA. Part 2: https://youtu.be/QqEjHZZiqAg.

Milton, D. (2012) ‘On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem.’.’ Disability & Society 27, 6 (2012): 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

Moeller H. G. (2021) ‘Luhmann & Cybernetic Identities.’ Undisciplined. January 2021. https://youtu.be/j5SaBSFApwc .

Moore, G.E. (1965) Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Electronics 38: 114–117.

Morgner, C. (2022) ‘Luhmann’s Evolution of Meaning.’ Undisciplined. December 2022. https://youtu.be/je97cYGO7k8 .

Nelson, T. (1999) ‘Ted Nelson’s Computer Paradigm, Expressed as One-Liners.’ Xanadu. https://xanadu.com.au/ted/TN/WRITINGS/TCOMPARADIGM/tedCompOneLiners.html .

Network Waitangi Whangarei (2012) Ngāpuhi Speaks. He Wakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni and Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Independent Report, Ngāpuhi Nui Tonu Claim.

Niaros V. et al. (2020) ‘Cosmolocalism: Understanding the Transitional Dynamics Towards Post-Capitalism.’ tripleC Communication Capitalism & Critique Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society. September 2020. DOI: 10.31269/triplec.v18i2.1188 .

nLab (2024) Higher Category Theory. https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/higher+category+theory .

Nonaka. I. et al. (2008) Managing Flow: A Process Theory of the Knowledge-Based Firm. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ostrom E. (2015) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Owen, H. (2008) Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Palmer, M. (2006) ‘Data is the New Oil’ ana.blogs.com. November 2006. https://ana.blogs.com/maestros/2006/11/data_is_the_new.html .

Pennington, P. (2023) ‘Amazon celebrated ‘ambitious partnership’ in letter to PM.’ RNZ. September 2023. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/498150/amazon-celebrated-ambitious-partnership-in-letter-to-pm .

P2P Foundation contributors (2023) ‘Main Page’, P2P Foundation. https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/index.php?title=Main_Page&oldid=136305 .

Rees, W.E. (2023) ‘The Human Ecology of Overshoot: Why a Major ‘Population Correction’ Is Inevitable.’ World 2023, 4, 509–527. https:// doi.org/10.3390/world4030032.

Reil, J. C. (1808) Beyträge zur Beförderung einer Kurmethode auf psychischem Wege. Halle : Curt.

Rushkoff , D. (2023) ‘The End of the Billionaire Mindset.’ SXSW. April 2023. https://youtu.be/3ryB_gjz0us .

Rushworth, S. (2024) ‘Prayer for the Earth: An Indigenous Response to These Times.’ The Poetry of Predicament. March 2024. https://youtu.be/anVEGa43xvM .

Schmidt, J. (2021) ‘Archiving Luhmann.’ Undisciplined. February 2021. https://youtu.be/kz2K3auPLWU .

Shiva, V. (1996) ‘Trading our lives away : Free trade, women and ecology.’ Durgabai Deshmuhk Memorial Lecture. Council for Social Development. https://csdindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/1996-Memorial-Lecture-Dr.-Vandana-Shiva.pdf .

Spicer, A. (2020) ‘Playing the Bullshit Game: How Empty and Misleading Communication Takes Over Organizations.’ Organization Theory, Volume 1: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787720929704 .

Strauch, T. (1989) ’Beobachter im Krähennest.’ WDR. https://youtu.be/qRSCKSPMuDc.

S23M (2023) ‘Collaboration and learning tools for the next 200 years.’ AutCollab.org.

Tohme, F. and Gangle, R. (2021) ‘Introduction to Luhmann & Systems Theory.’ GCAS Media. March 2021. https://www.youtube.com/live/pyp9r-TY7Mg .

University of Bielefeld (2024) ‘Niklas Luhmann-Archiv.’ https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/ .

Walker, N. (2013) Throw Away the Master’s Tools: Liberating Ourselves from the Pathology Paradigm.’ neurocosmopolitanism.com. August 2013. https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/throw-away-the-masters-tools-liberating-ourselves-from-the-pathology-paradigm/ .

Walker, N. (2014) ‘Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms & Definitions.’ neurocosmopolitanism.com. September 2014. https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/neurodiversity-some-basic-terms-definitions/ .

Kate Yoder, K. (2018) ‘War of words.’. Grist.org. December 2018. https://grist.org/climate/the-war-on-climate-the-climate-fight-are-we-approaching-the-problem-all-wrong/.

Yolles, M. (2021) ‘Metacybernetics: Towards a General Theory of Higher Order Cybernetics’ Systems 9, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems9020034.

You must be logged in to post a comment.