The growing cracks in the thin veneer of our “civilised” economic and social operating model are impossible to ignore, to the extent that serious discussions of degrowth are increasingly finding their way into mainstream media.

No day goes by without further examples of how the logic of capital, whether privatised or in the hands of the state, gets in the way of meeting essential human needs, or actively undermines any attempt to address the needs of the non-human inhabitants of planet Earth.

“Civilised” humans are so self-absorbed that they conceptualise Earth as “their” planet without blinking an eye. It is impossible to paddle back from this extreme position without acknowledging the collective delusion induced by our “civilised” way of life.

How do we go about to construct ecological niches that contribute to the thriving of life on Earth rather than taking away from it? We have triggered the sixth mass extinction, and biodiversity is declining at unprecedented rates.

What ecological role do we want to play going forward? Note that we have successfully disqualified ourselves from the absurdly anthropocentric role of “owner”.

Are we still capable of relearning of how to engage with other species at eye level? We might be able to learn quite a bit from other less self-absorbed species.

Industrialised “civilisation” has not only triggered the loss of biodiversity, it has even compelled us to pathologise humans that don’t seem to be able to cope with the demands of “civilisation”, such that increasingly children are labelled with “developmental disorders”.

“Civilised” neuronormative humans are so dependent on the security blanket of culture, that their attempt to maintain a culturally defined sense of “normality” results in a tiny Overton window that is so narrow that every sixth person is excluded, pathologised, and ideally subjected to normalisation therapies, to better fit into so-called “normality”.

Apparently humans are not only bent on reducing biodiversity via pesticides, insecticides, destruction of habitats, and green house gas emissions, we also seem to be bent on reducing the neurodiversity that is inherent in our own species. The industrial paradigm of “civilisation” critically depends on a reliable source of compliant culturally “well adjusted” conformists.

Sadly David Graeber died few weeks ago. The world could have benefited more from his line of inquiry into industrialised bureaucracy. Here is an extract from his brilliant first lecture at LSE in 2006:

Bureaucracies public and private appear—for whatever historical reasons—to be organized in such a way as to guarantee that a significant proportion of actors will not be able to perform their tasks as expected. It also exemplifies what I have come to think of the defining feature of a utopian form of practice, in that, on discovering this, those maintaining the system conclude that the problem is not with the system itself but with the inadequacy of the human beings involved…

What I would like to argue is that situations created by violence—particularly structural violence, by which I mean forms of pervasive social inequality that are ultimately backed up by the threat of physical harm—invariably tend to create the kinds of willful blindness we normally associate with bureaucratic procedures. To put it crudely: it is not so much that bureaucratic procedures are inherently stupid, or even that they tend to produce behavior that they themselves define as stupid, but rather, that are invariably ways of managing social situations that are already stupid because they are founded on structural violence…

Bureaucratic knowledge is all about schematization. In practice, bureaucratic procedure invariably means ignoring all the subtleties of real social existence and reducing everything to preconceived mechanical or statistical formulae. Whether it’s a matter of forms, rules, statistics, or questionnaires, it is always a matter of simplification.

Usually it’s not so different than the boss who walks into the kitchen to make arbitrary snap decisions as to what went wrong: in either case it is a matter of applying very simple pre-existing templates to complex and often ambiguous situations. The result often leaves those forced to deal with bureaucratic administration with the impression that they are dealing with people who have for some arbitrary reason decided to put on a set of glasses that only allows them to see only 2% of what’s in front of them…

It only makes sense then that bureaucratic violence should consist first and foremost of attacks on those who insist on alternative schemas or interpretations. At the same time, if one accepts Piaget’s famous definition of mature intelligence as the ability to coordinate between multiple perspectives (or possible perspectives) one can see, here, precisely how bureaucratic power, at the moment it turns to violence, becomes literally a form of infantile stupidity…

The question for me is whether our theoretical work is ultimately directed at undoing, dismantling, some of the effects of these lopsided structures of imagination, or whether—as can so easily happen when even our best ideas come to be backed up by bureaucratically administered violence—we end up reinforcing them.

Beyond Power/Knowledge : an exploration of the relation of power, ignorance and stupidity

David Graeber had a refreshingly down to earth and entrepreneurial approach to activism, which consisted of embarking on actions that seem appropriate to create a new reality (rather than simply engaging in civil disobedience) – and ignoring the established status-quo as needed to overcome crippling cultural inertia. He conceptualised the revolt of the caring classes and encouraged the activation of bureaucratically suppressed knowledge, i.e. the things that people are not allowed to talk about, into a power that can transform society.

I have a very similar philosophy. What I write about may at times seem abstract, but it always relates to concrete initiatives and services that I am involved with. This article connects some of the topics that I have written about in recent years with related services provided by S23M or the Autistic Collaboration Trust.

Paddling back from lethal forms of monoculture

Where to from here?

We live in a highly dynamic world, and our capability to understand the world we have stumbled into is quite limited. However, once we acknowledge our limitations, it is possible to learn from our mistakes, and also from the ways of life and the survival skills we cultivated in our pre-civilised past, which served us well for several hundred thousand years.

Our destination is beyond human comprehension, but ways of life that are in tune with our biological needs and cognitive limits are always within reach, even when we find ourselves in a self-created life destroying environment. All it takes is a shift in perspective, and corresponding shifts in the aspects of our lives that we value.

I have written about the various shifts in values that are currently in progress. The following sections contain extracts and link to articles with further details and background.

Shifting from independence to interdependence

Appreciation of humility

The notion of disability in our society is underscored by a bizarre conception of “independence”.

Humans have evolved to live in highly collaborative groups, with strong interdependencies between individuals and in many cases between groups. In our pre-civilised past all human groups were small, and interdependence and the need for mutual assistance was obvious to all members of a group.

The tools of civilisation, including money, have undermined our appreciation of interdependence, and within the Western world have culminated in a toxic cult of competitive individualism, which amongst the non-autistic population ironically leads to extreme levels of groupthink.

Celebration of interdependence

If you consider any potential outcomes beyond a ten year time horizon the current path of industrialised “civilisation” must be described as a form of collective delusion.

COVID-19 punched a big hole into the progress myth of of our “civilisation” and has exposed cultural practices that have substantially increased the risks of pandemics over the last 50 years.

At this stage our societies are still in the early stages of (re)learning essential knowledge about pandemics. The growing risks of much deadlier pandemics emanating from industrial animal agriculture practices, natural ecosystem destruction, and accelerating climate change (also leading to increasingly extreme weather events, crop failures, and resource conflicts) are not yet part of the public discourse.

To what extent human societies will experience famines, wars, and violent revolutions in the coming decades depends on two factors:

1. How many governments pro-actively and systematically discount the interests of capitalised busyness in favour of the immediate and the long-term (200+ year horizon) needs of human communities and ecosystems.

2. The extent to which human communities deploy easily (re)configurable digital technologies that are co-designed to meet local and bioregional collaboration needs, to serve as the backbone for non-violent “revolutions” in shared values, shared knowledge commons, and new (much less energy intensive and more collaborative and diverse) ways of living.

From collective delusion to creative collaboration

Shifting from transactions to trusted relationships

Appreciation of mutual trust

Autists are acutely aware that culture is constructed one trusted relationship at a time – this is the essence of fully appreciating diversity.

Society must start to move beyond awareness and acceptance towards appreciation of cognitive diversity. The topic of culture is a double edged sword. On the one hand a shared culture can streamline collaboration, but on the other hand, the more open and diverse a culture, the more friendly it is towards minorities and outsiders.

It is very easy for groups of people and institutions to become preoccupied with specific cultural rituals and so-called cultural fit, whereas what matters most for collaboration and deep innovation is the appreciation of diversity and the development of mutual trust. This is obvious to many autistic people, but only very recently has cognitive diversity started to become recognised as genuinely valuable beyond the autistic community.

What society can learn from autistic culture

Shifting from hoarding information to sharing of knowledge

Appreciation of mutual understanding

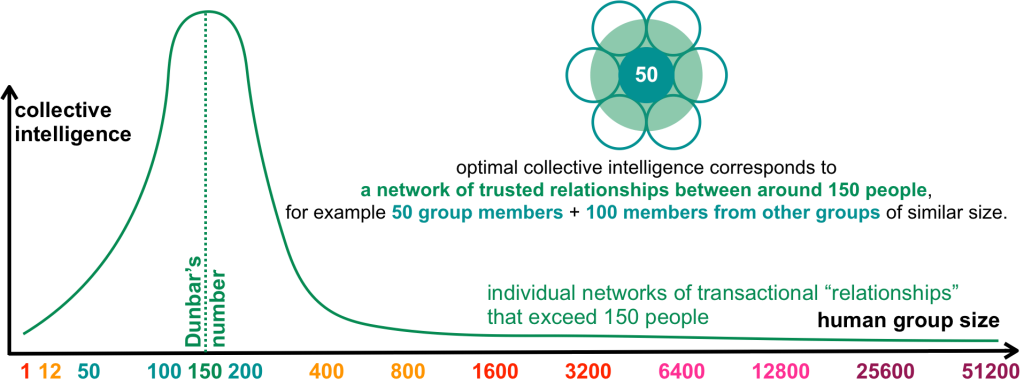

By definition, we don’t understand all the people that we “don’t relate to”. In our busy civilised and hyper-social lives we come across far more than 150 people (Dunbar’s number). We interact within them on a transactional anonymous basis, and we may read about their lives, but it is impossible for us to fully understand their context, as we have not walked in their shoes from the first day in their lives, and thus lack the experience, the insights, and the tacit knowledge that shapes their unique world-views.

Thus, making decisions that potentially affect the lives of many hundred to several billion people without explicit consent of all those potentially affected, must be considered the pinnacle of human ignorance and is a strong indicator of a lack of compassion.

Prior to the information age, for several hundred thousand years humans lived in much smaller groups without written language, money, and cities. The archaeological evidence available and also the evidence from “uncivilised” indigenous cultures that have survived until recently in a few remote places point towards an interesting commonality in the social norms of such societies:

The strongest social norms in pre-civilised societies were norms that prevented individuals from gaining power over others.

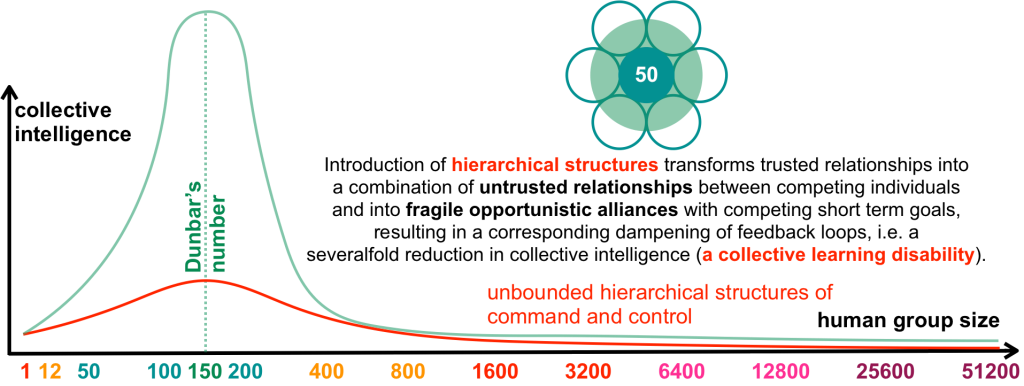

“Civilisation” can be thought of as a social operating system that is afflicted by a collective learning disability induced by primate dominance hierarchies, which dampen feedback loops and flows of valuable knowledge. The result is a cultural inertia that perpetuates social power gradients and that discriminates against the discoverers of new knowledge that might undermine established social structures.

The exciting aspect about the human capacity for culture is that via a series of accidental discoveries and inventions, we have created a global network for sharing valuable knowledge, as well as opinions and misinformation. It apparently takes a virus like SARS-CoV-2 to put this network to good use, and to shift “civilised” cultural norms away from profit maximisation and back towards sharing knowledge for collective benefit.

The dawn of the second knowledge age

The 10,000 year project of human civilisation or empire building is coming to an end. Human life as we knew it – shaped by the anthropocentric myths of meritocracy, technological progress, and growth – is less and less compatible with our daily experiences and with the needs of all the people and other living creatures that we care about.

Since the Cold War empires have increasingly shifted their focus from overt conventional war to economic warfare and psychological warfare. The growing economic power imbalance between the empires of the “developed” world and “less developed” nation states has significantly reduced the need for large scale direct military interventions to maintain imperial power structures.

The mainstream narrative of conventional, economic, and psychological warfare of course prefers framing of the same activities using the language of defending national interests, economic development, disruptive innovation, and achieving economies of scale.

Framing is the key tool for detracting from the many millions of human and non-human casualties.

The underlying common theme across all imperial cultures is the concept of cultural superiority, which results in a sense of entitlement and a perpetual drive to out-compete and over-power groups with different and “inferior” cultures.

Even though Western science likes to think of itself as ideology neutral it is not immune to ideological influence. The Western scientific worldview continues to be plagued by artificial discipline boundaries that significantly slow down the process of transdisciplinary knowledge transfer and the discovery of new insights that remain hidden in the deep chasms between established disciplines.

We need a language to reason about the cultural superiority complex of imperial societies and potential therapies and cures. Such a language is not only useful in biology, but also in all contexts that relate to human social behaviour and human activity within the context of biological ecosystems at all levels of scale.

The Human Lens provides thirteen categories that are invariant across cultures, space, and time – it provides an economic ideology independent reasoning framework for transdisciplinary collaboration.

The Human Lens concepts are recognisable in all historic human cultures, and they will continue to be relevant in another 1,000 years – this is what is meant by “economic ideology independent”.

A language for catalysing cultural evolution

Shifting from scarcity of resources to abundance of mutual aid

Appreciation of creativity

If neurodiversity is the natural variation of cognition, motivations, and patterns of behaviour within the human species, then what role do autistic traits in particular play within human cultures and what cultural evolutionary pressures have allowed autistic traits to persist over hundreds of thousands of years?

The benefits of autistic traits such as autistic levels of hypersensitivity, hyperfocus, perseverance, lack of interest in social status, and inability to maintain hidden agendas mostly do not materialise at an individual level but at the level of the local social environment that an autistic person is embedded in.

Within the bigger picture of cultural evolution autistic traits have obvious mid and long-term benefits to society, but these benefits are associated with short-term costs for social status seeking individuals within the local social environments of autistic people.

Many autistic people intuitively avoid copying the behaviours of non-autistic people. Life teaches autistic people that culturally expected behaviour often leads to sensory overload, and furthermore, that cultural practices often contain spurious complexity that have nothing to do with the stated goal of the various practices, such that a little independent exploration and experimentation usually reveals a simpler, faster, or less energy intensive way of achieving comparable results.

The unique human ability to adapt to new contexts, powered by neurodivergent creativity and the development of new tools, enabled humans to minimise conflicts and establish a presence in virtually all ecosystems on the planet. This level of adaptability is the signature trait of the human species.

Within “civilisation” autistic people tend to be highly concerned about social justice and tend to be the ones who point out toxic in-group competitive behaviours.

Autistic people are best understood as the agents of a well functioning cultural immune system within human society. This would have been obvious in pre-civilised societies, but it has become non-obvious in “civilised” societies.

Autism – The cultural immune system of human societies

Shifting from death by standardisation to celebration of diversity

Appreciation of uniqueness

In some geographies the prevalence of autism within the population is now estimated to be 1 in 35. Overall, in the US, according to CDC data, 1 in 6 children has a “developmental disability”, and in the UK, according to the Department of Education, 15% (roughly 1 in 7) of students have a “learning difference”.

I don’t have any issue with these numbers. In fact I am delighted that the extent to which people differ from one another is finally being recognised. But I do have an issue with the continuing pathologisation of people that don’t fit a standardised idealised (and hence fictional) human template. Even if we are seeing the first cracks in the pathology paradigm in relation to variances in neurocognitive functioning in the form of a partial shift from the language of disorder to condition and to difference, many of the traits associated with differences are still described in the pathologising language of diagnostic criteria.

The desire to categorise and standardise human behaviours is the underlying force of civilised societies, which reached new heights over the last 250 years, first with the mechanistic factory model of the world that defined the early industrial era, and then more recently, with the development of networked computers and with the emergence of automated information flows that currently shape significant parts of our lives and our interactions with people and with abstract technological agents.

Just because the majority of people, once they are fully programmed by our culture, perceives a growing minority of people (1 in 6) as not fully conforming to cultural expectations, does not mean that there is anything biologically or mentally wrong with these non-conformists. From a sociological and biological perspective the rising numbers of cultural non-conformists may just as well be seen as an indicator of an increasingly sick society characterised by cultural norms that are incompatible with human biological and social needs.

In our globally networked world individual inventors or small teams currently don’t have much if any control over the use of the technologies they create. Anthropocentrism and ignorance of human scale are the social diseases of our civilisation.

These diseases are obvious to most autistic people but they are only just beginning to be recognised by a growing number of people in wider society. Many signs are pointing towards a major cultural transformation based on a significant shift in values of younger generations that have grown up in an environment of continuous exploitation by technological monopolies.

Beyond peak human standardisation

Shifting from exponential growth to thriving life at human scale

Appreciation of collective intelligence

My working definition of intelligence: “finding a niche and thriving in the living world by creating good company, i.e. nurturing trusted relationships.”

In our world there is a silver lining to anything that reduces global – energy and resource hungry – busyness, like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Governments now have a unique chance to switch to a new understanding of economics, i.e regenerative management of resources and waste, that is compatible with human life on this planet – or otherwise to ignore the opportunity and lapse back into suicidal busyness as usual.

Our society could benefit a lot from a permanent cultural shift towards reduced commutes into city centres, from reduced global travel, and from increased levels of remote knowledge work. A pandemic might turn out to be an effective catalyst.

Ideas that are genuinely beneficial for society and the planet are best propagated by the slow and valuable process of knowledge sharing at eye level in Open Space, allowing for critical enquiry, independent validation, refinement where needed, and transmission of essential locally relevant context.

Using tools of persuasion beyond peer-to-peer learning may well become a taboo in the not-too-distant future. Capitalists are starting to trip over their own competitive games, desperate for new ways of remaining relevant in a post-capitalist world. The level of fear is illustrated by this headline: “Data is not the new oil – it’s the new plutonium”.

The vast majority of online social communication tools have been designed to support and promote the propagation of beliefs via the rapid process of influence rather than via the much slower process of evidence based learning and education. We live in a society driven by fear. Always ask who benefits from the fear. Fear can induce panic but it can also catalyse courage.

The cycle of fear can only be broken by the creation and replication of islands of psychological safety. Encouragingly the number of such islands is growing.

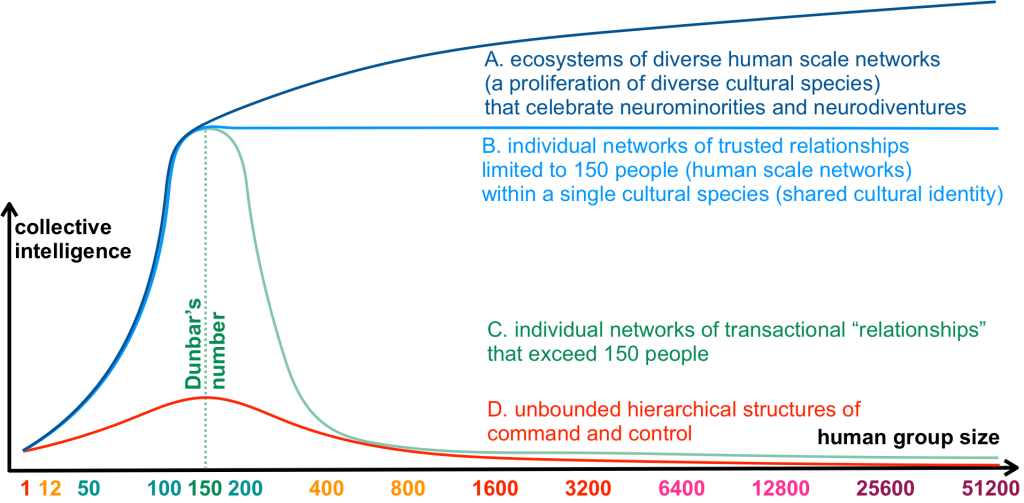

If we want to avoid repeating the mistakes of human “civilisations”, the rules for coordinating at super-human scale will have to allow for and encourage a rich diversity of human scale organisations. In a human scale social world, apart from the self-imposed constraint of human scale, there is no universally dominant organisational paradigm.

The resulting web of interdependencies can simply be thought of as “the web of life” rather than “civilisation 2.0”. We must not to again make the anthropocentric mistake of putting humans at the centre of the universe.

Organisations are best thought of as cultural organisms. Groups of organisations with compatible operating models can be thought of as a cultural species. The human genus is the genus that includes all cultural species.

Rediscovering human scale

In a transactional world, collective intelligence literally goes down the drain. In my experience, organisations with several thousand staff tend to act less intelligent than a single individual, and as group size grows further, intelligence tends towards zero.

The graph above assumes that as group size increases, people attempt to maintain more and more relationships – which end up deteriorating into transactional contacts with very limited shared understanding. The decline in collective intelligence can be avoided by consciously limiting the number of relationships of individuals, and by investing in trusted relationships between groups.

Hierarchical structures are inherently incompatible with the construction of trusted relationships within and between groups. Anyone who attempts to establish trusted relationships outside the hierarchical tree structure implicitly questions the effectiveness of the hierarchy, and thereby undermines one or more authorities within the structure.

The summary of existential risks in the following video is a good illustration of the full intelligence-destroying effect of hierarchical structures. Note that I don’t agree with the portrayal of the AI risks as being due to “superintelligence” – but I do see big risks. In the video the notion of “intelligence” remains undefined, and comparing different kinds of intelligence is like comparing apples and oranges, there is no linear scale.

If autistic people can’t always see the depth of the “bigger picture” of the office politics around us it does not in any way mean that we don’t see the big picture. In fact we are aware of the big picture and often we zoom in from the biggest picture right down to our immediate context and then back out again, stopping at various levels in between that are potentially relevant to our context at hand. Office politics only distract from the genuinely bigger context. Accusing autistic people of not seeing the bigger picture perhaps illustrates the social disease that afflicts our society better than anything else.

Neurodiversity friendly forms of collaboration hold the potential to transform pathologically competitive and toxic teams and cultures into highly collaborative teams and larger cultural units that work together more like an organism rather than like a group of fighters in an arena.

Time and trusted collaboration are our scarcest resources. The former is a hard constraint and the latter is the critical cultural variable on which our future depends.

We have reached a point where human societies can choose between a “collapse of human ecological footprint” based on a conscious and significant reduction of cultural and technological complexity or an “ecological collapse, including human population collapse” resulting from a perpetuation of the behaviours that are slowly but surely killing us all. Realistically both kinds of collapse will occur in parallel, and some communities may be able to avoid the latter form of collapse to a larger extent than others.

Regardless of what route we choose, on this planet no one is in control. The force of life is distributed and decentralised, and it might be a good idea to organise accordingly.

Learning how to create collaborative environments for small “human scale” groups (good companies) creates a collaborative edge over other companies as no effort is wasted on in-group competition. This in turn significantly reduces the need to spend time on “winning” direct competitions with other companies. What happens instead is that other companies are increasingly intrigued by the company’s capability.

Education is essential. When beliefs that represent evidence based facts are propagated via a critical self-reflective process of education that is at least one order of magnitude slower than the process of social transmission (imitation/copying without any deeper understanding), recipients – to a certain degree – are immunised against influence from those with opinions that contradict evidence based understanding.

Organising for neurodivergent collaboration

Shifting from quarterly results to 200+ year time horizons

Appreciation of endeavours that only deliver results for future generations

The catastrophic bush fires in Australia offer a good illustration of how people collaborate when confronted with the kinds of disasters that global heating will increasingly inflict on our societies.

The contrast between the mutual support that emerges within local communities and the behaviour of the most powerful person in the country is not surprising, but representative of a phenomenon that has been described as “elite panic”.

People are waking up to the fact that faith in leaders is what is likely to lead to the end of our species and countless other species. In the emerging social environment of disillusioned communities and citizens, you can neither buy trust nor investments that deliver a “return on capital”. Those who attempt it actually undermine their credibility and tie themselves to a sinking ship.

We are already much closer to a world without capital than capitalists would like us to believe. In many ways such a new world is much more desirable for most of us than the delusional world of infinite “growth” that we are still being sold.

From burning fossil fuels to burning capital

Human perception and human thought processes are strongly biased towards the time scales that matter to humans on a daily basis to the time scale of a human lifetime. Humans are largely blind to events and processes that occur in sub-second intervals and processes that are sufficiently slow. Similarly human perception is biased strongly towards living and physical entities that are comparable to the physical size of humans plus minus two orders of magnitude.

As a result of their cognitive limitations and biases, humans are challenged to understand non-human intelligences that operate in the natural world at different scales of time and different scales of size, such as ant colonies and the behaviour of networks of plants and microorganisms. Humans need to take several steps back in order to appreciate that intelligence may not only exist at human scales of size and time.

The extreme loss of biodiversity that characterises the anthropocene should be a warning, as it highlights the extent of human ignorance regarding the knowledge and intelligence that evolution has produced over a period of several billion years.

It is completely misleading to attempt to attach a price tag to the loss of biodiversity. Whole ecosystems are being lost – each such loss is the loss of a dynamic and resilient living system of accumulated local biological knowledge and wisdom.

It is delusional to think that humans are in control of what they are creating. The planet is in the process of teaching humans about their role in its development, and some humans are starting to respond to the feedback. Feedback loops across different levels of scale and time are hard for humans to identify and understand, but that does not mean that they do not exist.

A new form of global thinking is required that is not confined to the limited perspective of financial economics. The notions of fungibility and capital gains need to be replaced with the notions of collaborative economics and zero-waste cyles of economic flows.

Human capabilities and limitations are under the spot light. How long will it take for human minds to shift gears, away from the power politics and hierarchically organised societies that still reflect the cultural norms of our primate cousins, and from myopic human-centric economics, towards planetary economics that recognise the interconnectedness of life across space and time?

The big human battle of this century

Shifting from profitable busyness to good company

Rediscovering human potential and finding purpose in life

W.E.I.R.D. stands for Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic. As long as society confuses homo economicus with homo sapiens we are more than “a bit off course”.

The exploitative nature of our “civilised” cultures is top of mind for many neurodivergent people. In contrast, many neuronormative people seem to deal with the trauma via denial, resulting in profound levels of cognitive dissonance.

Earlier this year I attended an online course on collective trauma, and once the trauma inflicted by the structural constraints imposed by our civilisation was mentioned, many participants had the courage to acknowledge this source of trauma.

The evolution of W.E.I.R.D. cultures can be easily understood from an anthropological perspective or via the social model of disability.

To move forward, we need to align our social operating systems with a more optimistic – and less ideologically constrained – perspective on human potential.

As human interactions are increasingly mediated by digital technologies, this entails acknowledging the ideological inertia of our current technologies. The bias that is baked into many of our technologies transforms all human interactions into a bizarre competitive game of likes, followers, and views.

W.E.I.R.D. societies face a choice between:

(A) Co-designing and embracing a less W.E.I.R.D. digital technosphere that catalyses new forms of collaboration and that actively discourages toxic competitive games.

(B) Officially renaming our species to homo economicus, and relying on W.E.I.R.D. technologies to squash any ideologically inconvenient collaborative or altruistic human tendencies.

In terms of developing a more collaborative social operating system it turns out we don’t have to start from scratch.

Pathologisation of life and neurodiversity in W.E.I.R.D. monocultures

Cultural evolution allows human society to evolve much faster than the speed of genetic evolution, which is constrained by the interval between generations. However, within any given society, the vast majority of people only experience a very limited sense of individual agency. Gene-culture co-evolution has led to a mix of capabilities in a group where:

1. The beliefs and behaviours of the vast majority of people are shaped by cultural transmission from the people around them – the majority of people primarily learn by imitation.

2. A minority of atypical people is much less influenced by cultural transmission – this minority learns by consciously observing the human and non-human environment, and then drawing inferences that form the basis of beliefs and behaviours.

The extremely important role that culture has played and still plays in human evolution represents a transformational change in the mechanisms available to evolution – it is a major step in the evolution of evolution, comparable to less than two handful of other major steps such as the emergence of the first cells, the emergence of multi-celled life forms, the emergence of sexual reproduction, etc.

Cultural evolution allows the behaviour of human societies to evolve much faster than the behaviour of other complex life forms, to the point that our collective knowledge and medical technologies allow us to engage in an evolutionary arms race with various strains of microbes that used to represent a serious threat to human health.

Whilst in some domains humans have been able to harness our capacity for culture for the benefit of all humans, in other domains our capacity for culture has been used to establish and operate highly oppressive and stratified societies.

Autistic culture is minimalistic, able to accommodate profound differences in individual cognitive lenses, and it is the source of deep innovation.

Mental health statistics tell us that mainstream culture has diverged too far from autistic culture. In many organisations bullying has reached toxic levels. Trends in mental health statistics in the wider population hint at a problem far beyond the autistic community. Large parts of society are already paralysed by irrational fear of change, i.e. “the system is bad but at least it’s familiar”.

To move forward we need a system of language tools and interaction patterns that allow the people within small groups to increase their level of shared understanding.

The evolution of evolution

The objectives of the autism and neurodiversity civil rights movements overlap significantly with the interests of those who advocate for greater levels of psychological safety in the workplace and in society in general.

In the workplace the topic of psychological safety is relevant to all industries and sectors. Creating and maintaining a psychologically safe environment is fundamental for the flourishing of all staff, yet in most organisations psychological safety is the exception rather than the norm.

Given our first hand experience with innovation in these sectors and our involvement in autistic self advocacy and neurodiversity activism, the S23M team has decided to conduct a global survey on psychological safety in the workplace. The resulting data will be of particular interest for autistic and otherwise neurodivergent people who are experiencing bullying and more or less subtle forms of discrimination at work.

You can assist our effort by participating in the survey, and by encouraging your friends to participate in the survey.

In search of psychological safety

Tools for catalysing change

For our journey into the future we need appropriate tools for addressing challenges and needs over different time horizons.

Below is an overview of tools that I have been involved in developing. Many of these tools are available in the public domain and can be accessed free of charge by individuals and small companies. Please get in touch in case you have questions regarding any of these resources.

Short-range tools for survival

Mid-range tools for healthier lives

- UnConference on Interdisciplinary Innovation and Collaboration

- Trans Tasman Knowledge Exchange for the healthcare sector

- Community oriented and patient centric health service co-design

- Software services for catalysing collaboration across the healthcare sector

You must be logged in to post a comment.